New York, Paris — and Tokyo!

While the story of Antonio and Juan’s career is often focused on their connection to the streets and styles of New York and Paris, it would be a mistake to not recognize the huge influence and impact Tokyo had on the duo’s work from the early 1970s until the end of their lives.

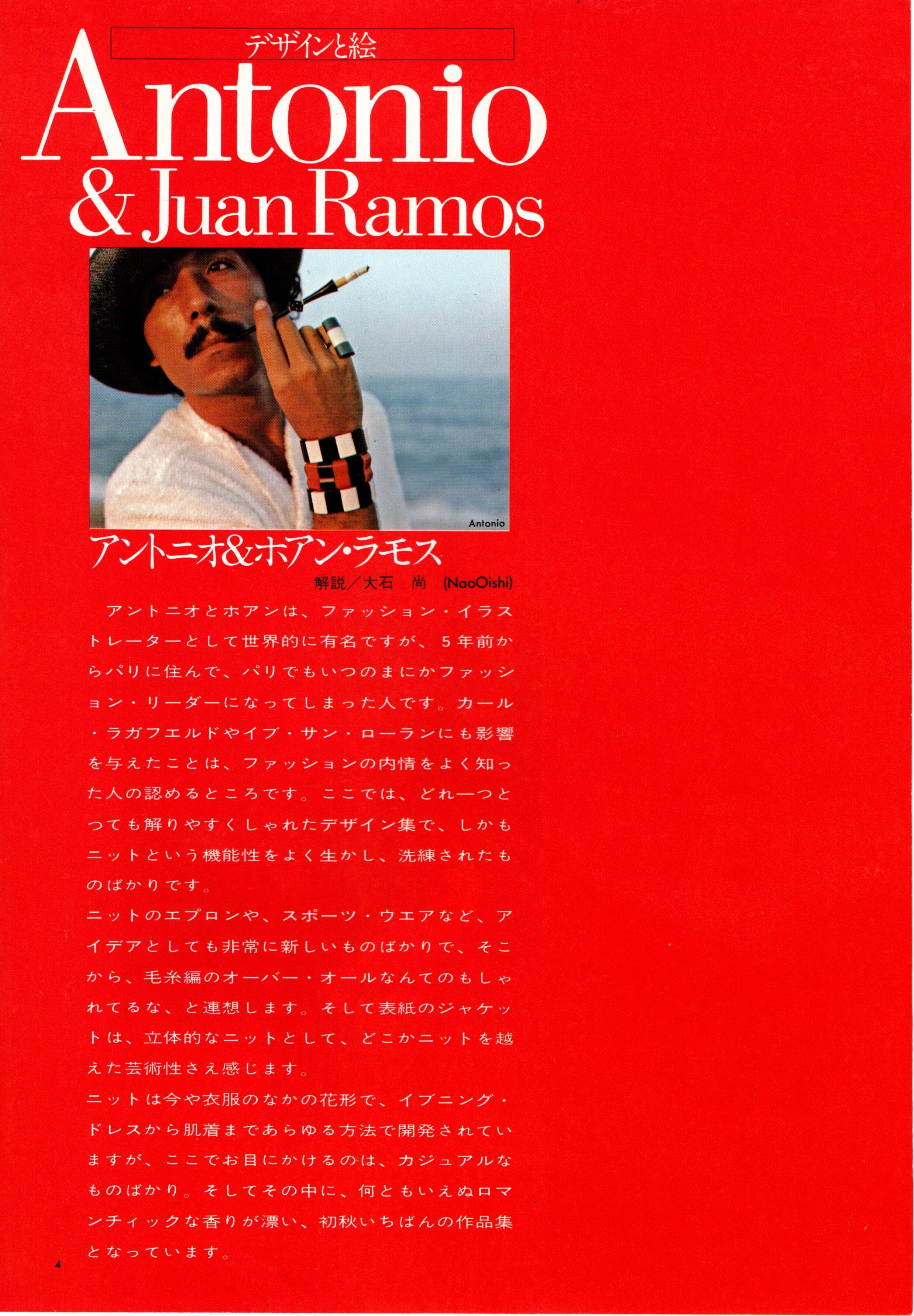

After gaining notable success in New York for their prolific illustration work, Antonio and Juan were introduced in the late 1960s to Charles Manzo, an American curator and art agent based in Tokyo, and his wife, Nao Oishi, a writer and fashion reporter. In 1969, the couple invited Antonio and Juan to visit them in Japan and the creative chemistry was immediate. Charles soon became their Asia agent, brokering commercial, editorial, and advertising projects, while also organizing exhibitions and lecture seminars. What followed was a collaboration that lasted more than 15 years. For the rest of their careers, Antonio and Juan returned to Japan regularly, often bringing models from America and Paris, and working out of makeshift hotel room studios.

Antonio working from a hotel room in Japan, 1969

Antonio and Juan in Tokyo, 1969

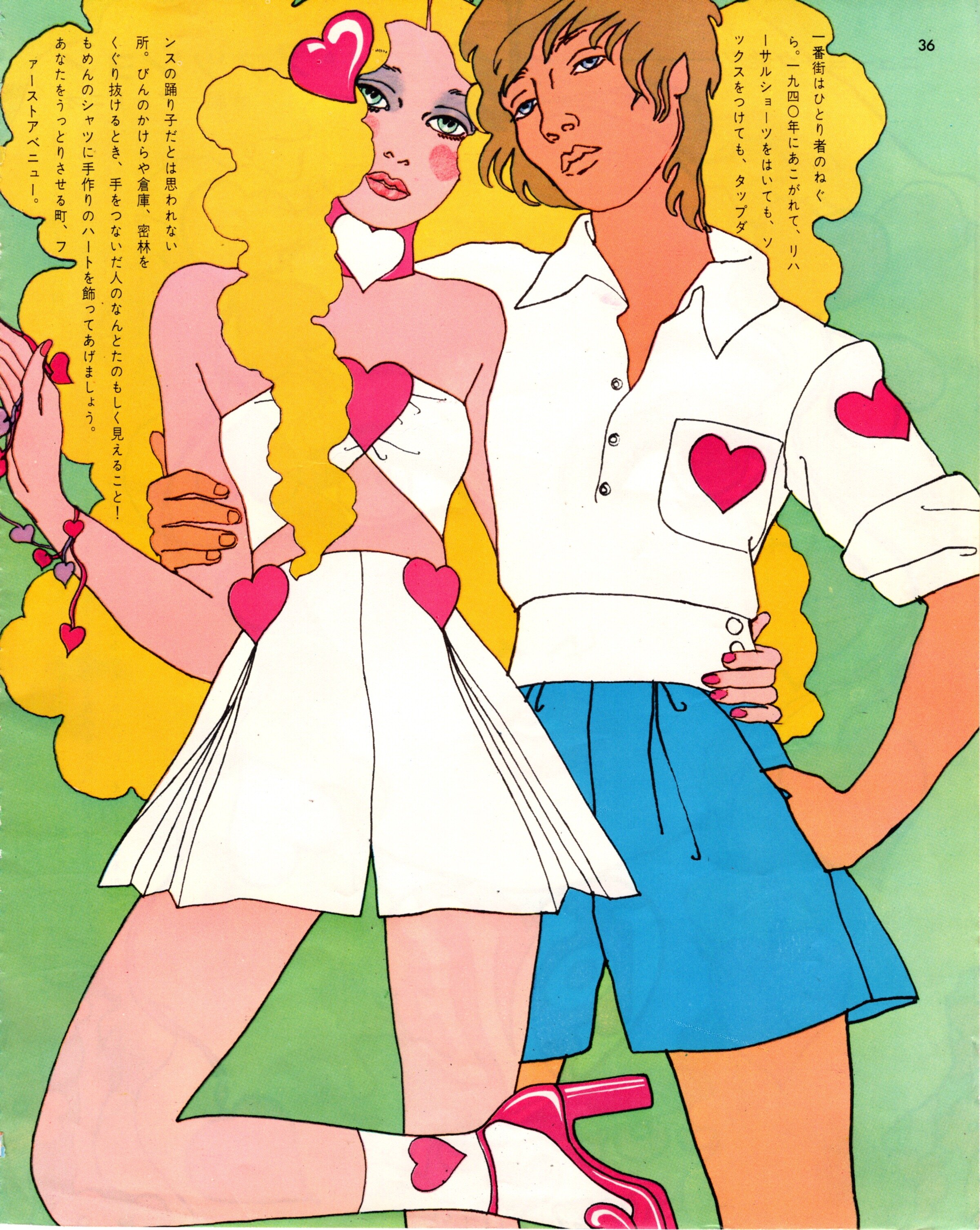

From the early 1970s onward, Antonio’s drawings appeared regularly in Japanese publications including Asahi Graph, Soen Magazine, Playboy, and Vogue Nihon. Branded as “New York artists,” their bold pop-graphic style resonated perfectly with the Americana craze sweeping Japan in the 1960s, propelling them to instant success.

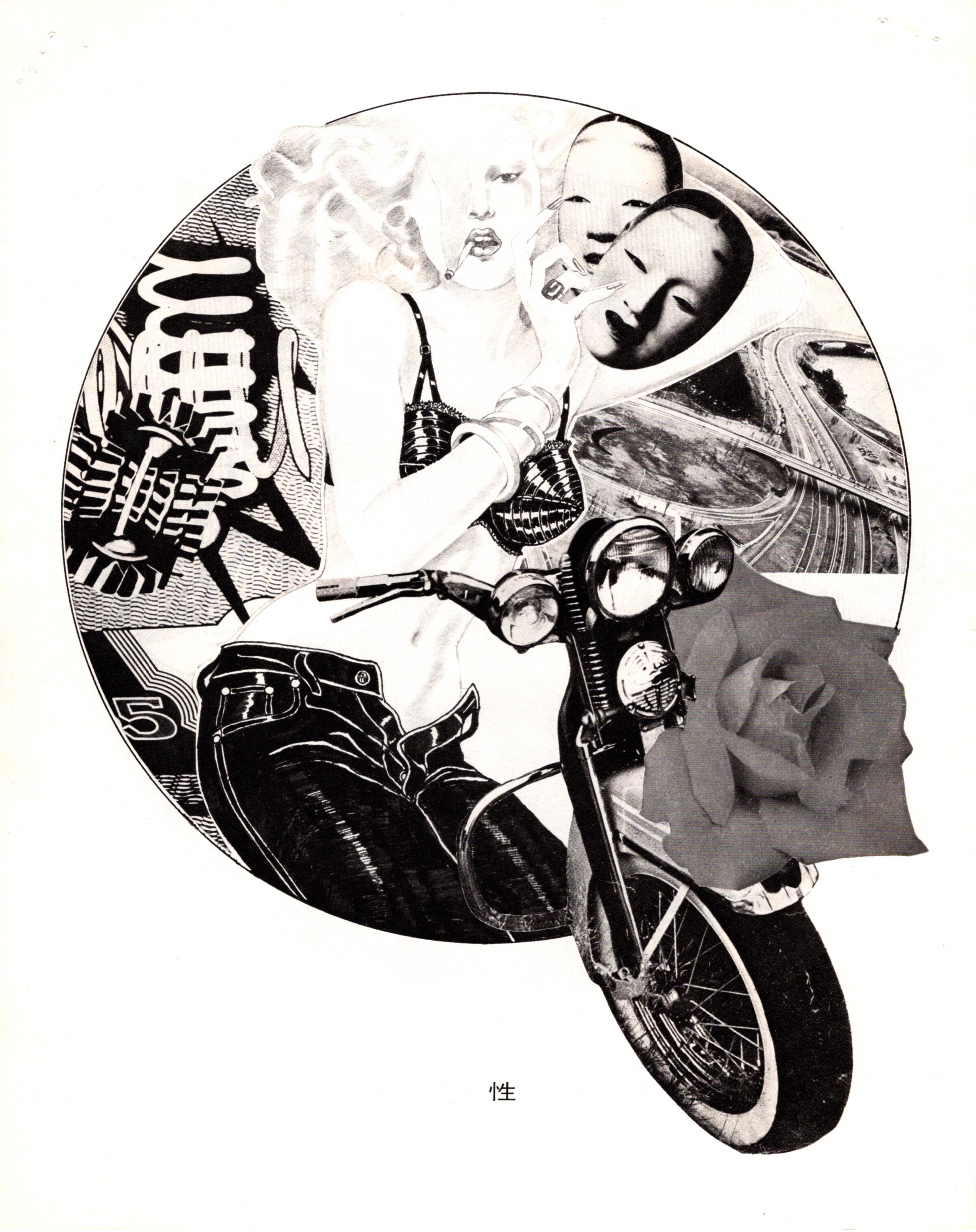

They also absorbed and reinterpreted traditional Japanese aesthetics, often borrowing techniques from Ukiyo-e, the Edo-period art form best known for its woodblock prints. The stylized female portraits, Kabuki drama, folk tales, landscapes, flora and fauna, and even erotica that defined the genre became rich sources of inspiration, which they fused seamlessly with contemporary fashion imagery. Unlike in the U.S. or Europe, illustration was widely embraced as fine art in Japan. Charles leveraged this to position Antonio and Juan’s work in gallery contexts parallel to their editorial rise. In 1970, five years before showing in their hometown of New York, they had their first solo exhibition at D.I.C. Gallery in Nihonbashi, Tokyo. Over the next decade, they presented seven more solo shows at institutions in Tokyo and Kyoto, including Matsuya Gallery, Odakyu Gallery, LaForet Museum, Wako Gallery Hall, Bunka Fashion College Museum, The American Center, and Seibu Gallery.

In tandem with these exhibitions, Antonio and Juan led multi-day seminars at prestigious schools such as Bunka Fashion College and Kuwasawa Art College, where they hosted lively drawing sessions and lectures on the history of fashion illustration. By the late 1970s and early 1980s, their focus shifted from editorial to commercial work and product lines. They created advertisements for pioneering department stores Daimaru and LaForet, as well as for heritage brands like Shiseido and Suntory Beer. As their popularity grew, “Antonio Lopez” emerged as a recognized brand in Japan, leading to collaborations such as a lingerie and packaging line for Wacoal, and an independent Antonio Lopez textile and scarf collection.

In the late 70s - early 80s, their focus shifted from editorial to commercial work and product lines. They created advertisements for pioneering department stores Daimaru and Laforet, and iconic Japanese heritage brands such as Shiseido and Suntory Beer. As their popularity grew, “Antonio Lopez” as a brand name began to gain traction, and Charles brokered collection deals with the lingerie company Wacoal for a line of underwear and packaging bearing his name, as well as an independent “Antonio Lopez” textile and scarf line.

Suntory Beer

A 1977 advertisement for Suntory Beer featuring Jerry Hall as an anthropomorphized bottle. Back in New York, Antonio and Juan were experimenting with their “ribbon series” photographs, which served as inspiration for both the concept and typography treatment of this work.

Laforet

In 1978, A & J created the inaugural campaign for Laforet, which had just opened its modern six story building located in the mecca of Japanese fashion and culture, Harajuku. This iconic store quickly became a beacon for youth fashion, housing over 120 stores with established and avant garde designers, as well as an exhibition space. Antonio and Juan designed a 5 season campaign (spring, summer, autumn, winter, and Christmas). Four of the drawings were inspired by Renaissance painters Sandro Botticilli and Giambattista Tiepolo, with highly detailed photorealistic renderings that replicated the colors and dynamism of nature with a classical full frontal flatness to the figures. The fifth drawings took inspiration for the German Bauhaus movement, riffing on Oskar Schlemmer's "The Triadic Ballet."

Antonio Lopez Scarves

In the late 1970s, after having achieved success throughout Japan, Antonio was commissioned to create a line of scarves bearing his signature.

The vibrantly patterned textiles took inspiration from art deco with bold lines, sweeping curves, geometric forms, and a nostalgic nod towards the celebration of the industrial age. Pictured here are two gouache studies.

Shiseido

Two pages from “The Antonio Artist’s Palette,” a range of custom color shades inspired by a curated list of influential 20th century artists, presented to Japanese cosmetics brand Shiseido in 1977.

From the presentation it reads, “ The proper use of make-up is an art in itself. We help all who use make-up become an artist by supplying them with palettes using color schemes of different artists, including Antonio’s.. The person who uses this make-up not only becomes an artist, but can achieve the “look” an any artist she chooses.

Wacoal

The “Antonio Lopez” line for Wacoal was produced in the late 1970s and included a range of bras and underwear constructed for a variety of women’s shapes.

The corresponding ad campaign featured a woman rising from a lily, a flower most commonly associated with purity and fertility.

Antonio created a scripted AL logo that was featured prominently on the underwear, and later designed for Wacoal a series of bath robes, pajamas, and house clothes adorned with his initials.

It was also in Tokyo in the early 1970s that Antonio met sisters Adelle Lutz and Tina Chow (née Tina Lutz). Half American and half Japanese, Tina became one of the most iconic “Antonio Girls,” embodying a rare beauty that was both glamorous and androgynous. Antonio would later introduce her to Michael Chow, and both he and Juan served as witnesses at their wedding.

Designer Kansai Yamamoto, model Sayoko Yamaguchi, and Antonio, New York City, c. 1980

Tina Chow wearing Fortuny, London, c. 1975

Their ability to access the Japanese market was aided by the rapidly expanding travel industry, which allowed them to move fluidly between New York, Paris, and Tokyo. At the same time, a wave of groundbreaking Japanese designers — Kenzo Takada, Issey Miyake, and Kansai Yamamoto among them — were establishing themselves in Paris and New York, fostering friendships and collaborations with Antonio and Juan.

This constant movement created a fertile ground for cross-cultural exchange. Ideas, fashions, and art movements flowed between cities, carried by people who embodied multiple worlds at once. Antonio and Juan’s genius lay in their ability to synthesize it all — the old and the new, the foreign and the familiar — into work that was unmistakably their own, no matter where it was seen.